Flatline weather.

After a particularly early snow in November 2019, I had high hopes for a robust white winter, full of scenic opportunities to get outdoors. Much to my disappointment, however, it’s been record-breaking ordinary and completely grey for months. I call it “climate flatlining.” Just dull and cloudy. According to our local meteorologist, you have to go back a decade to find a January as cloudy as last month. Likewise, February is dishing out the same thus far. The Vitamin D drain in my body is almost palpable and I’m longing to feel the least bit of sun soak deep into my skin once again. Landscapes have been rather boring around here to be honest and I’m anxious for something to change.

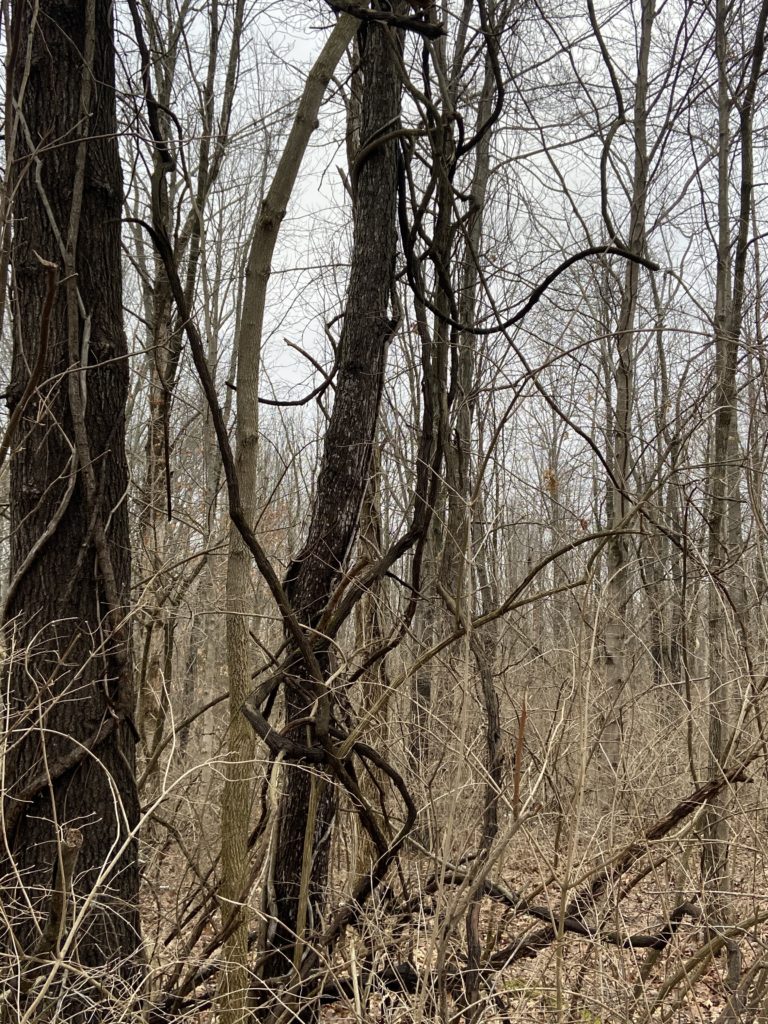

This ugly photo tells a sad story.

My husband and I have been land hunting for almost a year. As I’ve explored extensively within a 30-mile radius, I often came across parcels like the one in the photos above and below. Scrubby. Scraggly. Wasteful. Ugly. This got me thinking: should “forest management” be a concern for the private landowner or is it better to leave wooded areas alone and let nature take its own course? What techniques are there to prevent the mess above from occurring on my land? Can the average landowner intentionally manage wooded acreage on his/her own or does he/she need expert help to maintain a beautiful forest?

Responsibility often ignored

This land was farmed 60-80 years ago on a small scale, then sold, as the family farm came to an end. A rural developer put in a gravel lane and divided up the fields and woods into 5-15 acre plots. Most were sold off about 10 years later. It’s my guess that this land was allowed to grow up without any intervention or management and has had a hands-off approach for 50 years. Though a tree seed was able to reach maturity here and there, for the most part the weeds took over. Grapevines, Russian olive, honeysuckle and briars. There are so many invasive species today all across the United States, insects as well as plants. There’s hardly a place on earth that is not touched by something that wasn’t meant to be there.

As God intended

God planted and tended the Garden of Eden, then He gave Adam the privilege and responsibility to be steward over it. It’s the original purpose and job of mankind. However we are to work in co-operation with God’s natural laws, not design our own. There is a fine line between tending, correcting, protecting nature and doing too much to upset the perfect balance and health of nature. There a place for both the management and the hands-off approach. Wisdom is knowing when and where to do each.

History of Forest Management

Our American landscape looked much different 400 years ago when the Pilgrims landed and many of the Native Americans led nomadic lives. In the early 1600s, forests covered about one-half of the continental United States (Source: http://www.appalachianwood.org/forestry/quantity.htm). While we usually think of pre-colonial forests being wild and unmanaged, I think that’s a false assumption. The Native Americans had a huge affect on the health and sustainability of our forests.

Annual burning was a common practice of many native tribes for a number of reasons. They burned hillsides to improve the grasses there so that deer and elk would frequent the area and could be hunted easily. Increased grass production also provided more grasses for basketry. By burning the forest understory, openings in the canopy were produced which allowed acorn-bearing oaks to grow better. Acorns were a major source of food for the Native American and attracted deer. Regular burning is also thought to have reduced insect infestation, not only providing a bug-free space to set up a nomadic village, but ensuring better quality acorns. At the very least, burning around villages provided a fire break and reduced the potential of accidental fires, protecting their homes. Intervals between fires are thought to have been between 11-15 years, mimicking the natural occurrence of forest fires from lightning.

In the 1850’s European descendants in America developed the mindset of preventing fires at all cost. This fire suppression has led to a build-up of forest debris, overcrowding, disease, insect infestations and too much dead wood left on the forest floor. The current practice of suppressing fires, along with unusually dry summers and mild winters, has contributed to the catastrophic fires we see in the California, the southwest and parts of MT, WY and CO. (Source: https://www.savetheredwoods.org/blog/forest/native-american-use-of-fire)

Wild Grape

Above is a tangled mess of grapevines choking out small and large trees on the same property mentioned above. Wild grape is a highly aggressive, invasive species. The typical wild grapevine can damage trees by breaking limbs, bending trunks and shading tree leaves. They add mass to the top of a tree making it susceptible to ice and wind storms. If not stopped, grapevines can kill trees.

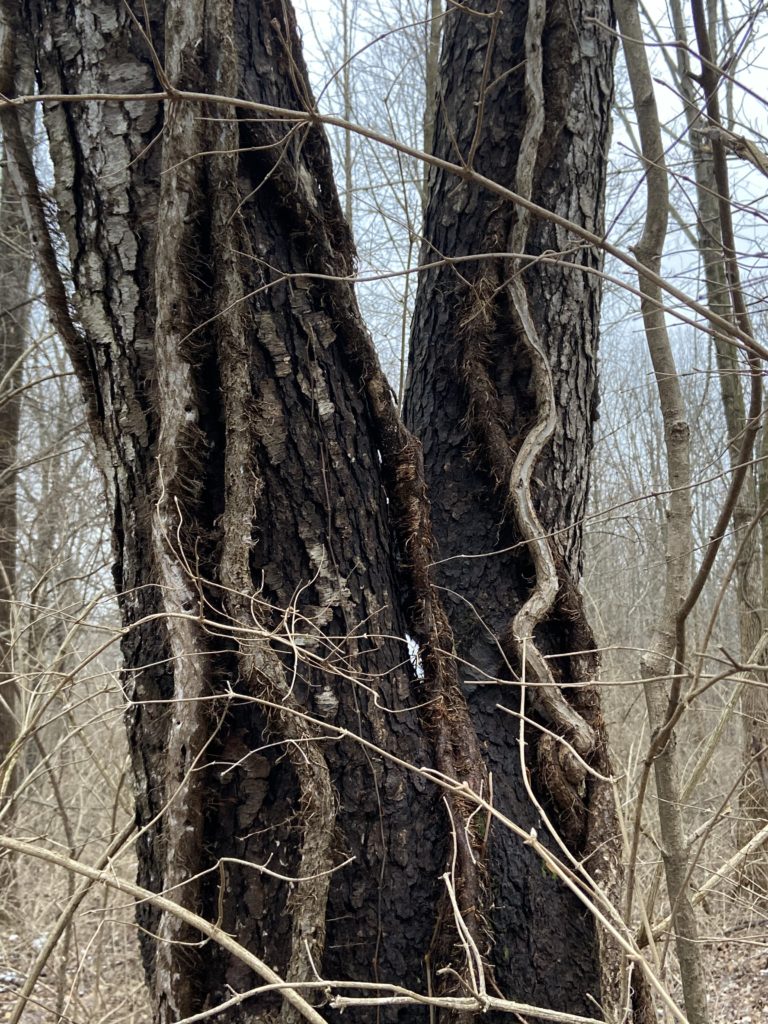

Even the bigger trees, like the one above, are stressed by virginia creeper and poison ivy vines due to lack of nutrients and sunlight. A matter of two cuts completely through each vine would solve this problem and allow the tree to flourish.

Not a good healthy environment for this tree.

We’re losing whole species

Above and below is an elm tree. If you live anywhere east of the Mississippi, you’ve likely heard of Dutch Elm Disease. It is annihilating the elm populations much like the blight did to the chestnut tree at the turn of the 20th century. One quarter of the hardwoods in the Appalachian Mountains were chestnut trees. In the 1800’s most barns and homes east of the Mississippi River were made from it and chestnuts were a valuable commodity of food. Remember the line from a Christmas song “Chestnuts roasting over an open fire.” Who has ever eaten a chestnut today? Around 1904 a chestnut blight arrived on US shores due to imported lumber and in a few short years, the chestnut tree was nearly wiped out. Today, only a few have been painstakingly grown solely for genetic purposes. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chestnut)

Our family sees something very similar as we camp in the Rocky Mountain States during the summer. The pine beetle has wiped out millions of acres of Ponderosa and Lodgepole pine. Whole mountain sides are brown from dead trees. A century of fire suppression is one of the main contributing factors.

Dutch Elm Disease

The Dutch Elm Disease is actually caused by 2 or 3 kinds of fungi that are passed from tree to tree by the elm bark beetle. The loss of outer bark, shown below, is due to woodpeckers knocking off pieces of bark in search of the beetles. From a distance the tale-tell sign of discoloration is usually an infected elm tree. It can be treated at an early stage, but often harvesting and burning the wood is the only way to stop the spread of the disease.

Below on the same tree, the outer bark is completely gone and the inner bark has been damaged by some animal. Notice the evidence of scraping the inner bark with claws or antlers. This area is about 3-4′ off the ground.

For Comparison

You might compare the photo below with the first ones I posted in this blog. Notice a difference? The undergrowth of weedy plants is missing. There is a mixture of very old growth, medium-aged trees and new saplings, thinned enough to allow sunshine and nutrients to all. A thick layer of leaf mulch on the forest floor will break down and feed the forest root system. I don’t know if this woodlot has been intentionally managed or not but it’s a great example of a healthy hardwood forest.

Below is a photo of a silvopasture from this site. Silvopasture management mixes hardwood woodlots with forage areas. Unfortunately, too many farms allow cattle to roam unmanaged in wooded areas, resulting in severe damage to soils and vegetation, and creating opportunities for non-native plant species to infiltrate. In a silvopasture, grass seeds are sowed on the woodland floor and trees thinned to allow enough light for the grasses to thrive. Rotational grazing with smaller livestock is ideal for this kind of forest management. This management is more complex, labor intensive and time consuming but quite productive for both the farmer and nature.

I haven’t even addressed the subtopics of forest fire management, management of wildlife habitats (as encouraged by organizations like Pheasants Forever or Quail Forever), erosion management, or water conservancy and wetlands management, which I know very little about. There’s a lot included in this area of forest management and I am thankful for those who study these topics. The sad state of the wood lot at the beginning of this post has certainly spurred me to know more so I can be a good steward of this incredible creation God has given us.

Honestly I have never given forest management much thought before. But as I think back on my childhood living in a healthy hardwood forest, my father harvested a lot of downed timber and cut diseased wood out. We even (unintentionally) had a forest fire when I was two years old that burned a lot of the understory. Living next to a university-owned Research Forest now, I have seen them burn the understory in the spring. You would think the trees would catch fire but they don’t! Here’s a basic explanation of different methods of forest management: https://www.ncforestry.org/teachers/forest-management-basics/

I’ll leave you with a few shots of some critters who came by my way recently. Grey squirrel was scavenging for dropped bird seed from the feeder. Check out those furry ears and the rusty colored stripe along his side!

Red-tailed Hawk was sunning himself on a cold morning, watching the grasses below for mice. I see him often in this area, about a mile from our home, as I drive to town. Below Mama Doe is in the rear, staying alert, while her teenage twins are in front. They like the molasses apple mineral salt block we get at Tractor Supply Company. At dawn and dusk they come close to the house eating acorns under the large oak trees in the front yard.

Thanks for stopping by. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts and experiences on forest management in the comment section at the bottom of this blog.

Forecast calls for sunshine tomorrow – I’m counting the hours. Too bad it’s only going to be 10°F with 20mph winds. Don’t think I’ll feel much warmth.

From my neck of the woods to yours, catch ya later!

Carolyn

So very interesting, Carolyn— info I would never know on my own!

And, your photos always ” tell stories “! Thank you!!!

Really interesting post! I learned so much while reading and it was really amazing to see the difference between the two photos of a “healthy” and an “unhealthy” forest. Since I have grown up my whole life in a “healthy” forest I had no idea they could look that bad! I also really enjoyed learning about the Indians. I never thought about all the different ways they would took care of the land. I really enjoyed reading your blog!

Very interesting, Carolyn, also VERY sad. I am sorry you are having this huge problem. Bishop Woods behind my house on Bennett Road was a wilderness, but after marjiwana paraphenalia was found they totally cleared out the woods except for the oak trees. We were able to see the traffic on 9th st. It was so sad. As a result we lost all of the deer.